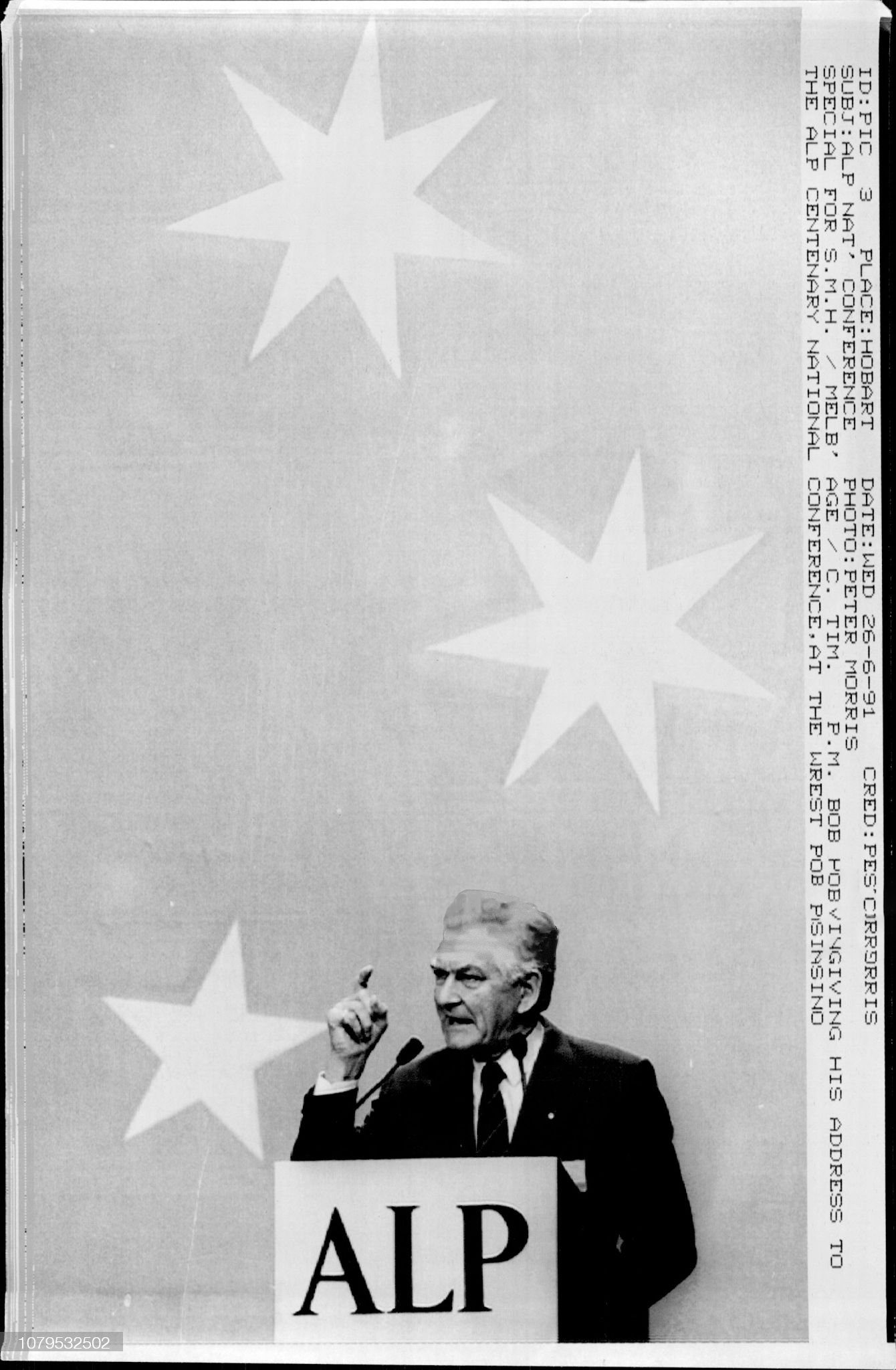

The Australian Labor Party celebrated its centenary in June 1991 at a national conference in Hobart. It pledged itself to hold a referendum, before the centenary of Federation, to make Australia a republic, and to legislate indigenous land rights. Keating supporters had seen the conference as an ideal opportunity for Hawke to ‘go gracefully’ - announce his retirement amid the plaudits of a grateful party. Instead, Hawke delivered a fighting speech which made clear his intention to fight and win the 1993 election with a reinvigorated reform agenda. In November, with the economy still flatlining and unemployment above 10%, Hawke and Kerin issued a ‘jobs statement’ providing modest support for education, training and other stimulatory measures.

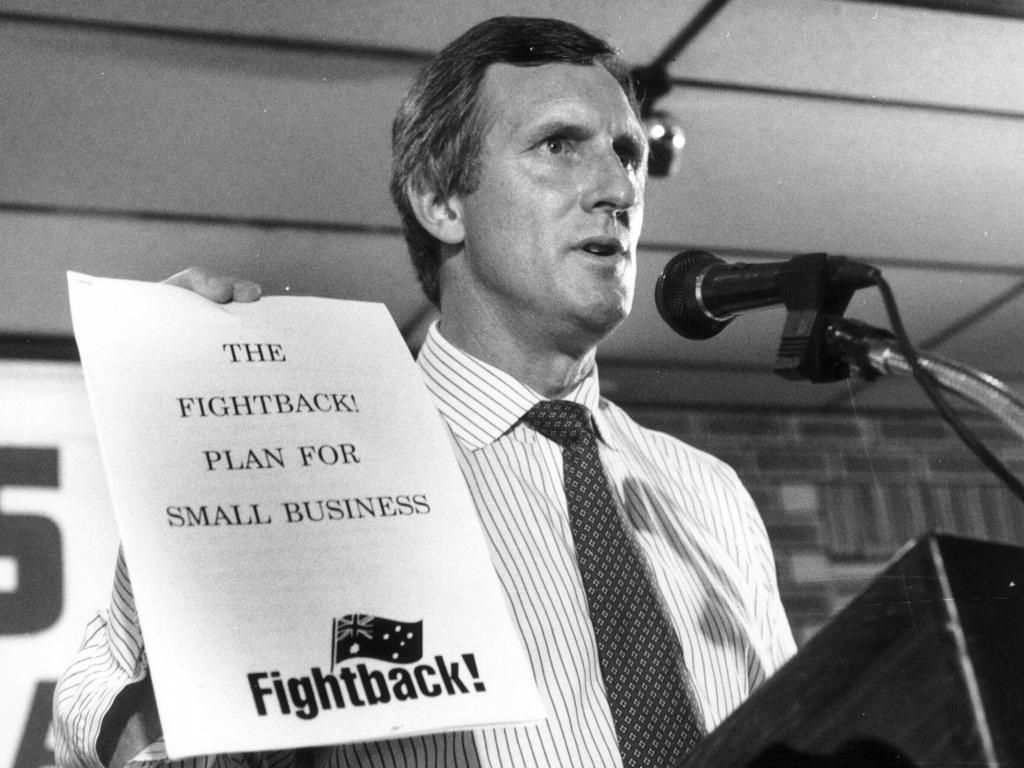

While the recession and leadership struggle weakened the Prime Minister and the government, the Opposition’s political fortunes improved. The Liberal Party had brought the Peacock-Howard-Peacock merry-go-round to an end, selecting a new leader after the 1990 election: John Hewson, classically-trained economist and investment banker, had entered Parliament in 1987. In November 1991 Hewson launched ‘Fightback!’, a radical 650-page manifesto that promised further privatisation, dramatic spending cuts, the elimination of protection, and major tax reform including the introduction of a tax on consumption – a 15% Goods and Services Tax (GST). Hawke had struggled to land a blow on this unexpected Liberal foe, and ‘Fightback!’ gave Hewson an immediate bounce in public opinion polls. The sacking as Treasurer of a confidence-sapped Kerin further eroded Hawke’s position in caucus. Unemployment hit 10.5%. A renewed Keating challenge seemed inevitable.

At a special meeting Caucus meeting on 19 December, Hawke declared his position vacant; in an election to fill the vacancy, Keating defeated Hawke 56 votes to 51. Keating was sworn in the next morning, by Governor-General Bill Hayden, while Hawke performed his last official duty: handing over to the custody of Parliament House the bark petition he had received in 1988 from the Barunga community. Galarrwuy Yunupingu, chair of the Northern Land Council, stood on as Hawke tearfully set out, once more, a path to reconciliation.

Paul Keating had at last attained the post he had aspired to for his entire career in politics – but he had just over a year before the next election to turn around the government’s fortunes.

In a limited reshuffle, the now Prime Minister Keating appointed close ally John Dawkins as Treasurer, and began preparations for a major economic statement in the New Year. ‘One Nation’, delivered by Keating in February, was designed to decisively accelerate economic recovery through Keynesian intervention: notably, through increased infrastructure spending and lump sum payments to family allowance recipients. A return to surplus and sharply reduced unemployment was promised over four years. The prize was the promise of income tax cuts in the next term of government. Essentially paid for by bracket creep, these cuts were designed to neutralise those offered as sweeteners under ‘Fightback!’, leaving Hewson to defend the 15% Goods and Services tax as a standalone.

Meanwhile Keating hosted official visits by US President, George H W Bush in early January and the Queen in February, using the occasions to set out two major themes of his Prime Ministership. With Bush, he pushed for yet closer engagement with the Asia-Pacific region, and proposed the APEC ministerial meetings be elevated to Heads of government level; Bush demurred, but Keating pursued the idea in Jakarta in April with Indonesian President Suharto.

The Queen’s visit prompted Keating to speak of a growing sense of national purpose and identity; criticised by the Opposition for allegedly showing disrespect to the monarch, Keating berated them in parliament for hankering after a so-called golden age in the 1950s,

‘when Australia stagnated … when vast numbers of Australians never got a look in; where women did not get a look in and had no equal rights and no equal pay; where migrants were factory fodder; where Aborigines were excluded from the system; where we had these xenophobes running around [talking] about Britain and bootstraps; and that awful cultural cringe under Menzies which held us back for nearly a generation.’

Keating then gleefully proposed Hewson and Howard be installed as museum exhibits in the old Parliament House, before branching out into a new line of attack on their cultural cringe

‘to a country which decided not to defend the Malayan peninsula, not to worry about Singapore and not to give us our troops back to keep ourselves free from Japanese domination. This was the country that you people wedded yourself to, and even as it walked out on you and joined the Common Market, you were still looking for your MBEs and your knighthoods, and all the rest of the regalia that comes with it.’

The bravura performance delighted his caucus and put the Opposition on notice for the election ahead. But the economy refused to respond to the stimulus of ‘One Nation’. Unemployment topped 11% in July and economic growth slowed once more. Unions, concerned about job losses caused by Labor’s previous tariff cuts, pushed for a tariff pause, but agreed once more to defer wage claims and thereby lock in low inflation. Superannuation was further extended with the Superannuation Guarantee legislation, requiring employers to make contributions to a super fund on behalf of their employees; the legislation covered female workers as well as male, lifting to over 70% the proportion of workers with retirement savings.

Confronting Native Title and Re-election

In June 1992 the High Court issued a historically transformative judgement, finding in favour of Eddie Koiki Mabo and a group of other Torres Strait Islanders who claimed traditional ownership of land in the island of Mer.

The Court rejected the colonialist conceit that, at the time of English settlement in 1788, the continent of Australia had been ‘terra nullius’ – that is, empty land that belonged to no-one and was thus available to be annexed by the Crown. Instead, the land and seas had long been subject to the traditional custom and laws of the indigenous people under what the Court called ‘native title’. Further, the Court found, where native title had not been legally extinguished by subsequent forms of land title, it continued to exist: Mabo and the others did own their land, and the Australian judicial system had finally recognised it.

Against this background, Keating became the first Prime Minister to acknowledge the devastation wrought by European settlement on the life and welfare of indigenous Australians. In a speech at Redfern to mark the International Year of the World’s Indigenous People, Keating declared that it was

‘we [non-indigenous Australians] who did the dispossessing. We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life. We brought the disasters, the alcohol. We committed the murders. We took the children from the mothers. We practiced discrimination and exclusion.’

Keating also continued to reinterpret Anzac Day commemorations, shifting the focus away from Gallipoli, which he saw as part of an imperial past, to Kokoda where, he argued, Australians had fought and died in defence of its independent future in a new world. Visiting Kokoda in April 1992, he dropped to his knees and kissed the ground.

Labor continued to target ‘Fightback!’, attacking cuts to Medicare and other social spending, and talking up the threat to job security represented by a shift to individual employment contracts. Having himself advocated a consumption tax in 1985, Keating insisted that Labor’s subsequent years of disciplined fiscal repair meant such a tax was no longer needed and - regressive, inflationary and liable to stifle growth – certainly not appropriate in the 1990s. By year’s end Hewson was forced to modify his package, exempting food from the GST and proposing an infrastructure fund. The contest between the two leaders became intensely personal; but Keating had the sharper barbs. In one Question Time in September, Hewson taunted Keating: why won’t you call an early election? Keating’s response: ‘The answer is, mate, because I want to do you slowly. There has to be a bit of sport in this for all of us. … There will be no easy execution for you.’

Keating waited until the New Year, and called the election for 13 March 1993. He promised to boost childcare for working women with an innovative tax rebate for work-related childcare, and his policy speech in Bankstown promised progress towards a republic with an Australian as head of state. Ably supported by campaign manager and ALP National Secretary Bob Hogg, Keating wrestled to keep the focus on the GST.

For his part, Liberal leader John Hewson struggled with the complexity of his package, and in a disastrous television interview failed to explain how it would affect the cost of a birthday cake. Labor was returned, its primary vote restored to 44.9% and picking up a net two seats for a comfortable majority of 13. Hewson lost what had been almost universally billed as an ‘unlosable’ election. After ten years and four terms of Labor government, the win was a supreme triumph for Keating, now elected for the first time in his own right as Prime Minister.